A comparison of DNA ethnicity results for four members of the same family reveals unexpected variety! Here’s how genetic phasing affects ethnicity.

Your DNA ethnicity results from the various DNA testing companies, also called admixture results, are like the short film before the actual feature presentation. The short film is entertaining, and certainly keeps your attention for a while. But the feature presentation in this case is your genealogical match list, which is SO much meatier when you engross yourself in it.

However, those ethnicity results can become more interesting when you have several members of the same family tested, so you can compare their results.

Comparing DNA ethnicity within a family

Let’s take a look at the four members of the Reese family. Before they even take the test, the Reese family has something to their great advantage: their family history indicates that they are mostly from Western Europe. This is a big advantage in the climate of today’s ethnicity results as all of the testing companies have far more data in their reference populations pouring out of western Europe than from anywhere else. That means that in general, they are going to be better at telling you about your heritage from Ireland or England than they are at discovering that you are from China or India.

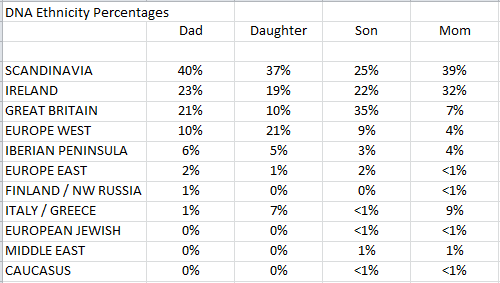

Looking at the ethnicity results for the Reese family, we are tempted to start applying our knowledge of DNA inheritance to the numbers we see:

We know that each child should get half of their DNA from their mom, and half from their dad. So our initial reaction might be to look at the dad’s 40% Scandinavian and mom’s 39% Scandinavian and assume that the child would also be about 40% Scandinavian with 20% from dad, and 20% from mom. You can see that the daughter did in fact measure up to that expectation with 37% Scandinavian. But the son, with only 25%, seems to have fallen short. The temptation to consider the daughter as the far better example of familial inheritance is strong (especially for us daughters, who are so often exceeding expectations!), but of course inaccurate. It is actually very difficult to look at the parents’ numbers alone and estimate the percentages that a child will receive.

Here’s a short video explaining why siblings have different ethnicity results

Remember that these numbers are tied to actual small pieces of DNA we call SNPs (snips). Of the near 800,000 SNPs evaluated by your testing company, less than half of them are considered valuable for determining your ethnicity. The majority of the SNPs tested are working to estimate how closely you are related to your genealogical cousin. A good SNP for ethnicity purposes has to be ubiquitous enough to show up in many individuals from a given population, but unique enough to only show up in that population (and not any other populations). It is a difficult balance to strike.

But even when good SNPs are used, it is still difficult for the computer at your testing company to make accurate determinations about your ancestry. Take the Great Britain line in the Reese family data, for example. The dad has 21%, the mom 7%, so it would follow that the largest amount any child could have would be 28%. We see the daughter (of course!) falling well within that range at 10%, but the son is seven points above at 35%. How does THAT happen?!

Let’s go back to some basic biology. Remember that you have two copies of each chromosome, one from mom and one from dad. These chromosomes are made up of strings of letters denoting the DNA code. That means that at each SNP location you report two letters: one from mom and one from dad. As the testing company is lining these letters up for comparison, they have to decide which letters go together: which are from the same chromosome, which set came from one single source.

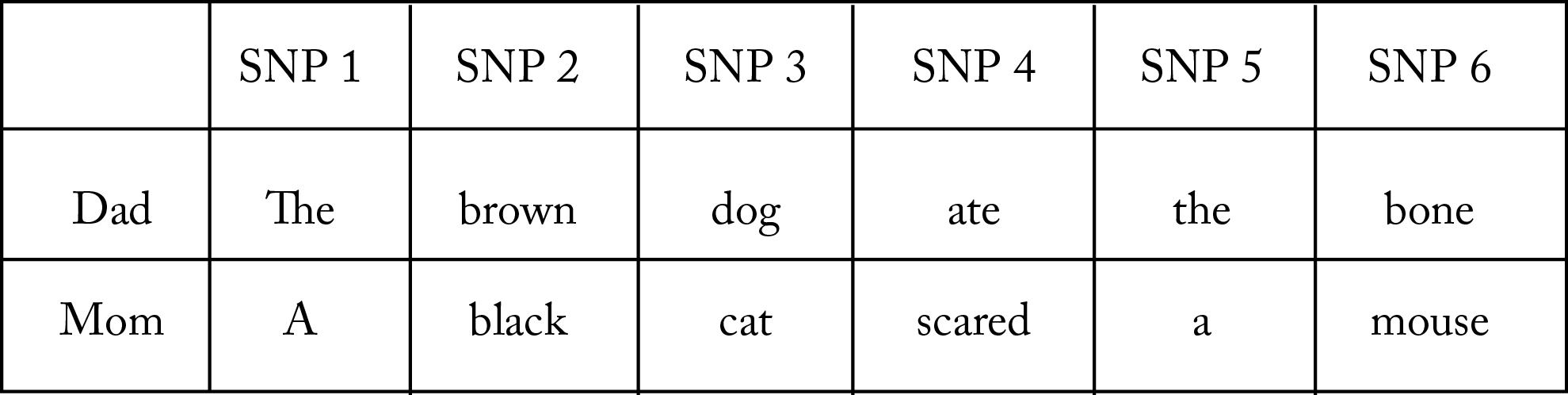

To illustrate how this works, let’s say we are trying to write two sentences: “The brown dog ate the bone” and “A black cat scared a mouse” where each word in each sentence represents a SNP. However, all the computer sees are two words, it doesn’t know which word goes in which sentence. So for the first word we have two choices “The” or “A”. Perhaps in this case it wouldn’t make all that much difference which one we chose, as they both might mean approximately the same thing. But mixing up other words words creates entirely new sentences with very different meanings. For example, instead of the correct “A black cat scared the mouse” we might end up with the incorrect “The brown cat ate the mouse.” Which has a very different meaning.

You can see in the example below that it would be fairly easy to get it wrong. Mixing up a couple of the words creates entirely new sentences with very different meanings!

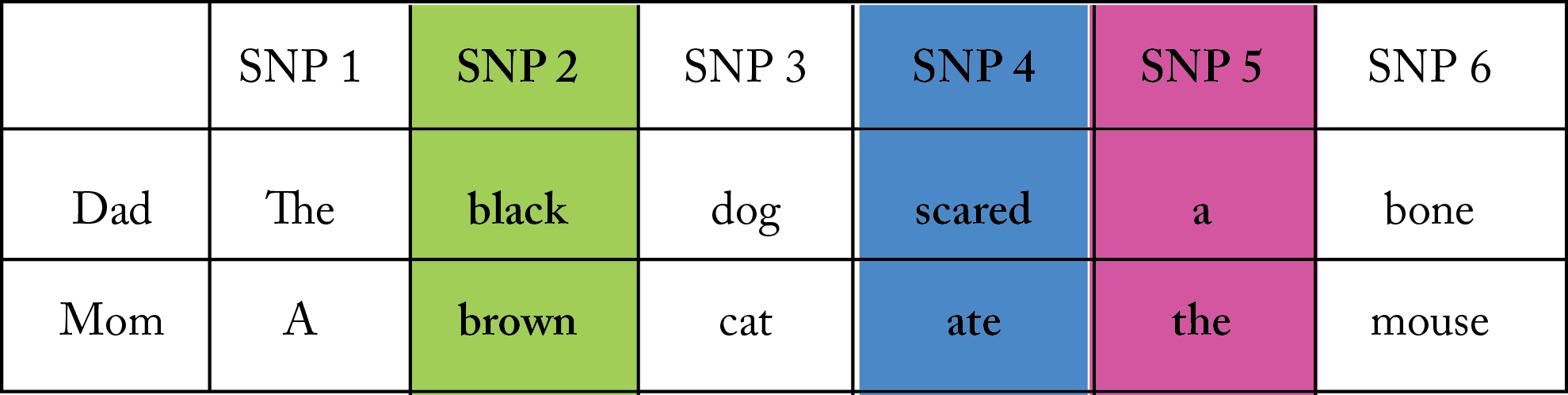

This one gets it right:

This one, not so much:

Genetic phasing at work

The process of determining which set of values goes on which line is called phasing. Often the inconsistencies you see in your DNA test results, whether it be in the matching or in the ethnicity, are because of problems the company has with this very difficult process.

While it is not valuable to your genealogical research to have children tested when both parents are tested, it is fun to compare notes to see who got what. We can also very tangibly see the fleeting nature of this DNA stuff. We can see that in one single generation this family has lost all traces of ancestry to several world regions. This really highlights the value of having the oldest generation of family members tested, to try to capture all that they have to offer in their DNA code. Plus, DNA testing can involve members of your family who are not genealogists, like the “Reese” family son. He’s interested in the larger picture of who he is in the world, and that’s the part of the Reese family history he’s taking with him—and contributing—at this point in his life.

Ethnicity results in action!

There’s lots to learn about ethnicity results and it can be hard to know where to start. That’s why we’ve compiled our free Ethnicity Quick Start guide. You’ll learn applicable tips for how to use your DNA ethnicity results and feel like a pro in no time!

Get A Free Guide to DNA Ethnicity Results

An earlier version of this article was originally published at www.geneaologygems.com.