Identifying enslaved ancestors can be so challenging. These 7 tips will help you use DNA (as well as traditional research) more effectively when researching African ancestors on your family tree.

Recently, Donise Smith Lei contacted Your DNA Guide for some coaching. She was putting the finishing touches on her new book, Delving into My Bitterroots: How I Resurrected My Enslaved Ancestor, Granvill, and So Can You. Before going to press, she wanted an expert review of the way she’d applied DNA testing results to identifying her 3X great-grandfather, Granvill, who was enslaved.

Recently, Donise Smith Lei contacted Your DNA Guide for some coaching. She was putting the finishing touches on her new book, Delving into My Bitterroots: How I Resurrected My Enslaved Ancestor, Granvill, and So Can You. Before going to press, she wanted an expert review of the way she’d applied DNA testing results to identifying her 3X great-grandfather, Granvill, who was enslaved.

With her permission, we share the following tips that came out of her coaching session with Diahan Southard. We hope these tips will help others who are searching for the identities of enslaved ancestors, because we recognize that this can be so challenging. Very little identifying documentation survives pertaining to most enslaved people. Silence about slavery prevented many stories and facts from being passed down, both within families and within communities where slavery was present.

Tips for Using DNA To Help Identify Enslaved Ancestors

1. Start with the best family tree you can.

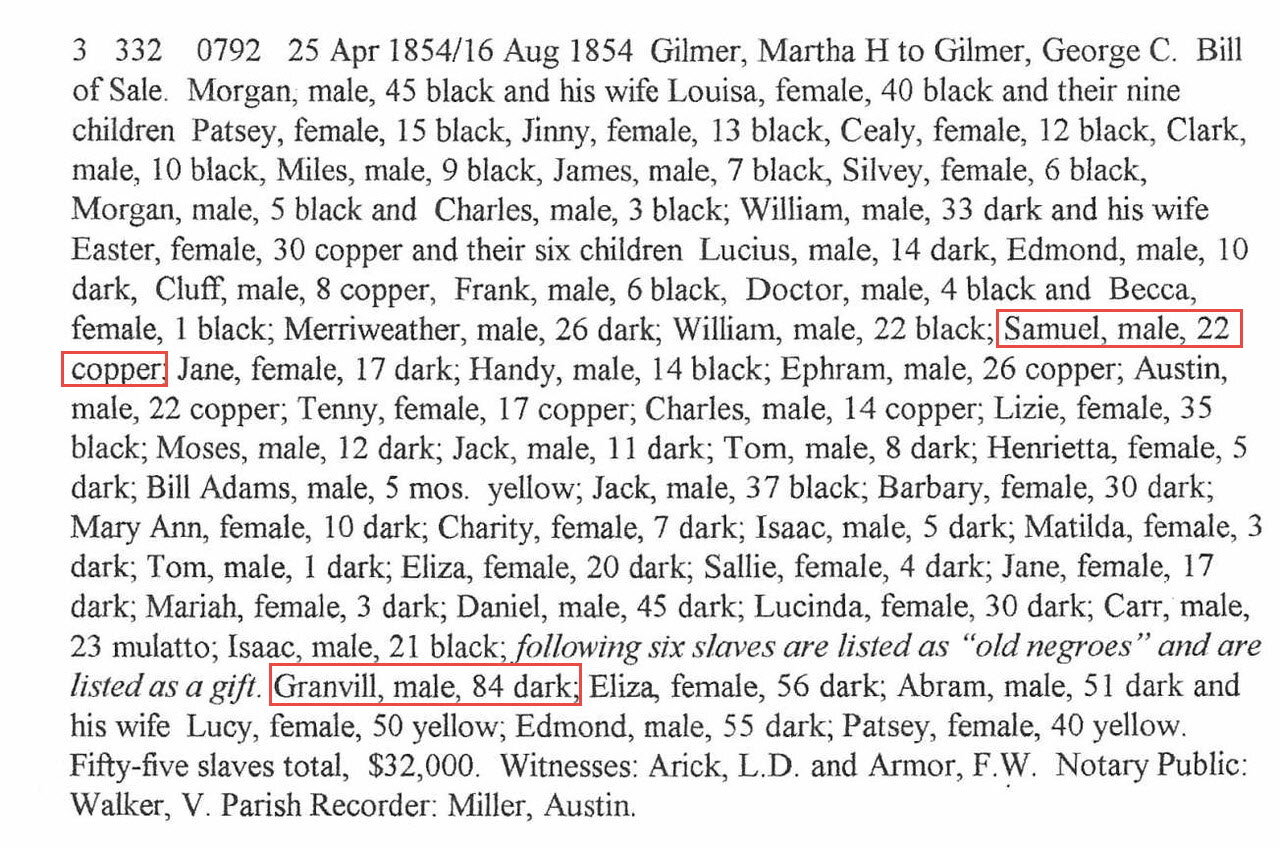

Donise began researching her family history well before DNA testing was an option for her. She followed her family tree back to her 2X great-grandfather, Samuel. Then she found a document showing the sale of 55 enslaved people. Samuel appears here, and so does an 84-year old man named Granvill:

The name Granvill caught Donise’s eye because Samuel’s oldest son was named Granvill, too. Could this be Samuel’s father?

Donise discovered that other researchers have attributed several children to Granvill. “I have the circumstantial evidence that all [Granvill’s known] children say he was born in Georgia, which is where the slaveholder family lived in the 1780s,” she continues. She noticed the same naming pattern in these families. Several named their oldest son Granvill. In fact, throughout this large family, a total of 17 descendants appear to be named after him.

The repetition of Granvill’s unusual name down through the generations is probable evidence of this man’s importance to this cluster of people, whether they were biologically related or not. Given the absence of available vital records to tie them together, this may be one of the strongest documentary evidences of Granvill’s paternity.

Historical records can’t always fully or accurately reconstruct a family tree, and that’s especially true when researching enslaved ancestors. That’s where DNA comes in.

2. Use autosomal DNA testing, but understand its limits.

“From a genetic perspective, Donise is right on the edge of what autosomal DNA can reach,” says Diahan. “The 3X great grandfather is about as far back as we can go. The DNA supports—it never proves—at this level. When we are dealing with cousins that far back, we will inevitably be dealing with small amounts of DNA. With small amounts of DNA, our biggest enemy is confirmation bias (meaning, she has a theory, we see a bunch of people who share DNA with her whose genealogy fits the theory, we declare the theory ‘proven’ with DNA).”

For greater reach into the past, test the oldest living generation. (Here are some tips on getting them to test.) That’s what Donise is doing. Even though she’s tested herself, she has used her dad’s autosomal test results when working with matches. That means she’s actually using DNA to look at the great-grandparent generation—a more reasonable task for autosomal testing.

3. Compare genetic v. genealogical relationships.

“To make sure we are interpreting the DNA as accurately as possible, we first need to check the genetic vs genealogical relationships,” says Diahan. “Is the amount of DNA being shared between matches consistent with the genealogical relationships you’ve assigned them? If possible, examine the amounts of DNA they are all sharing with each other to make sure that is also consistent.”

Donise reports on her analysis. “I have multiple DNA matches with descendants of 7 out of 8 of Granvill’s children,” she says. “I have a huge cluster of relatives that AutoCluster with him as the common ancestor [she used the Genetic Affairs AutoCluster tool; there’s also an AutoClusters tool on MyHeritage].” This means that these matches are related to one another, too.

She closely explored relationships between herself and a set of possible fourth cousins, whose DNA relationships supported that relationship. “The data is in line with the range of 0 – 127 shared cM for 4th cousins, with an average of 35 cM,” she wrote in her book. “My DNA cousins were also 4th cousins to everyone else (except on their direct lineages).” She notes further consistency with descendants from a half-sibling, whose “numbers are consistent with half relatives.”

4. Use WATO to calculate probable relationships.

Something Donise hadn’t done was use DNA Painter’s free tool, What Are the Odds? Diahan suggested she use this tool to help confirm, statistically, the odds of her DNA matches belonging in certain places on their shared trees.

“I had never used [WATO] before (or even thought to use it) because it was not helpful for what I wanted, I thought,” she said. “Everything I read said you use the WATO tool to figure out if this is your relative. Since I knew they were my relatives, why would I use that tool? But after she told me I should use it, I tried to use it.”

As someone who loves math, Donise describes using WATO as an “a-ha” moment. She compares it to mathematical proofs. “Let’s say James is not my 4th cousin,” she says. “I put him in as my 3rd, 4th, and 5th cousin. Then I put in all the data from my other cousins. Putting him at 4th cousin worked, whereas the other places didn’t work (or caused a contradiction in geometry). Thus, James has a high probability to be my 4th cousin.”

Just a word of caution about using the WATO tool. It works best when you are dealing with individuals sharing at least 40 cM.

5. Use Y DNA testing to learn more about paternity.

Documenting paternity can be particularly challenging when researching enslaved people. In the United States, it was illegal for enslaved people to marry; paper trails largely don’t exist for their unions. Enslaved partners couldn’t choose to stay together (they might be sold away or forbidden to see their loved one). Furthermore, it wasn’t uncommon for enslaved women to be raped—with no documented consequences for the perpetrator.

To learn more about paternity, Diahan’s advice is for Donise to get Y DNA from male descendants of the genealogically-documented sons of Granvill. “That would go a long way to showing there was a consistent YDNA signature among those believed male descendants, including her Samuel.”

What if all of them did have a shared father, but it was a white man (like an enslaver) rather than Granvill? Y DNA testing can provide hints. Matches may point to a larger family group that could eliminate one possibility or the other. So might the haplogroup, which points to a region of origin for that line. Donise did Y-DNA testing with a couple of cousins believed to descend from Granvill on their paternal line. Those results pointed toward West Africa as their distant ancestral homeland.

6. Double-check your match’s trees.

AncestryDNA ThruLines tree reconstruction tool supported Donise’s theory about her relationships to her DNA matches through Granvill. However, that tree reconstruction tool can only use the tree data it’s given. What if your match’s tree is wrong?

“Don’t forget to evaluate the documentary evidence behind your matches’ trees,” says Diahan. “Be sure they all belong on the places where their trees (and ThruLines) is putting them.”

7. Collaborate with your matches whenever you can.

Diahan spends a lot of time teaching people how to reach out to their DNA matches. You can sometimes learn a lot more from each other if you can exchange questions—and share whatever answers you each have.

Collaboration is especially critical when trying to identify enslaved ancestors, says Donise. “I spoke to several of my DNA cousins today and they all reiterated the same point. We could not have figured this out if we were not collaborating. Each of us got to the point of finding their ancestor in the 1870 US census but it literally took us working together for about 6 months before we understood the DNA and figured out that Granvill was our common ancestor.” She credits one of her matches with first noticing that Granvill was a share name on a few of their trees.

“Every once in a while someone did pass down a story or bit of information that helps put the puzzle pieces together,” Donise continues. She shares an example: one of her matches knew about a diary that helped them identify their family’s enslaver. Another knew about when Samuel (Donise’s own 2x great-grandfather) died, because that event made her match’s grandmother an orphan at age eight.

Choose YOUR Next Steps

Ready to find to find out more about your ancestors? Take a look at our free guide, 4 Next Steps for Your DNA. We’ve compiled all our best information on how to move forward once you’ve gotten your DNA results back.