Your best family tree for DNA matches should be bursting with siblings, cousins and other relatives. Here’s how to use census records to construct a more robust family tree.

The best family tree for working with your DNA matches includes all your grandparents’ brothers and sisters (and siblings of great grandparents, etc). These siblings may be the ancestors of your DNA matches. If you can place these siblings (and even their descendants) on your family tree, you can often make it easier to identify your connections to your matches.

The best family tree for working with your DNA matches includes all your grandparents’ brothers and sisters (and siblings of great grandparents, etc). These siblings may be the ancestors of your DNA matches. If you can place these siblings (and even their descendants) on your family tree, you can often make it easier to identify your connections to your matches.

How do you figure out who your ancestor’s siblings were? Obituaries often reveal family names and relationships. However, you can’t always find obituaries on your relatives, and they’re not always complete. So, when possible, use census records to reconstruct an ancestor’s entire family group. Even if you’ve looked at census records before, read over the example and the half-dozen tips below to better understand what census records may be telling you (or not telling you) about your family relationships.

Finding family groups across census records

In the United States, England, Wales and some other countries, periodic census records provide a documentary snapshot of who was living in your ancestor’s household at the time. In the United States, federal censuses are taken every 10 years on the years ending in “0” (including in 2020), and are available from 1940 back to 1790, except for almost all of the ill-fated 1890 census. In England and Wales, look for censuses every 10 years between 1841 and 1911 (and for 1921, after privacy protections expire in January 2022), and also explore the 1939 Register.

These censuses cover the perfect timeframe for DNA-matching family trees, since autosomal testing will identify many (not all) of your relatives within the past 4-6 generations.

Usually, you’ll look for relatives in more-recent censuses first, as older people, and then trace them back in time, since genealogists work from the knowledge of more recent decades into the unknown past. Below, I’ll show you how my ancestor Washington McClelland appears in census records beginning with his childhood in England, and then in his adulthood in the United States.

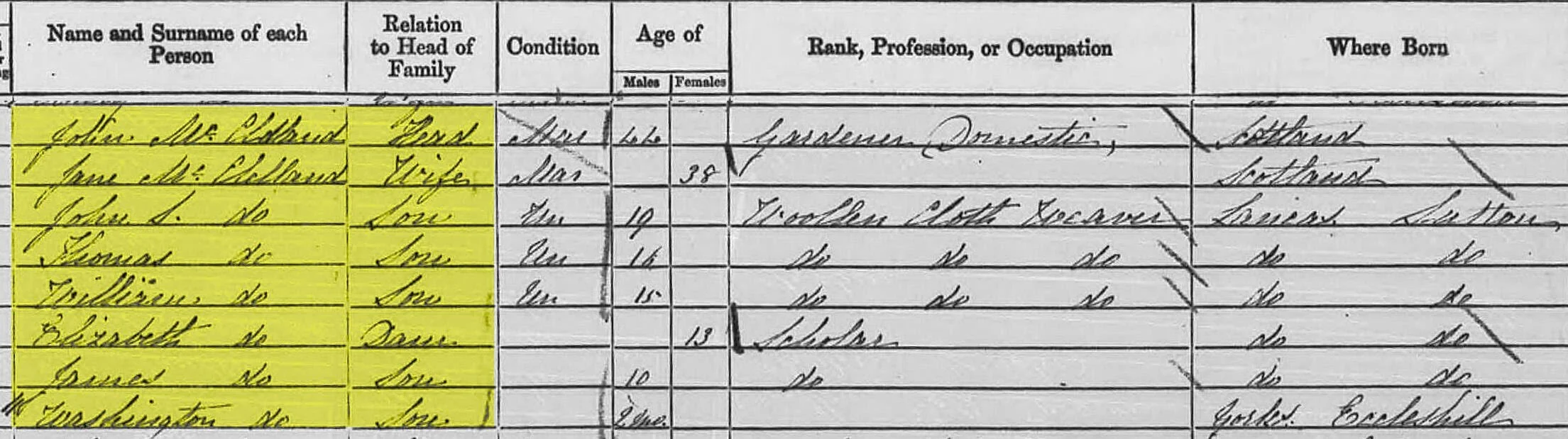

England’s 1861 census was taken just after Washington was born. He’s the baby listed here, beneath five older siblings and both his parents:

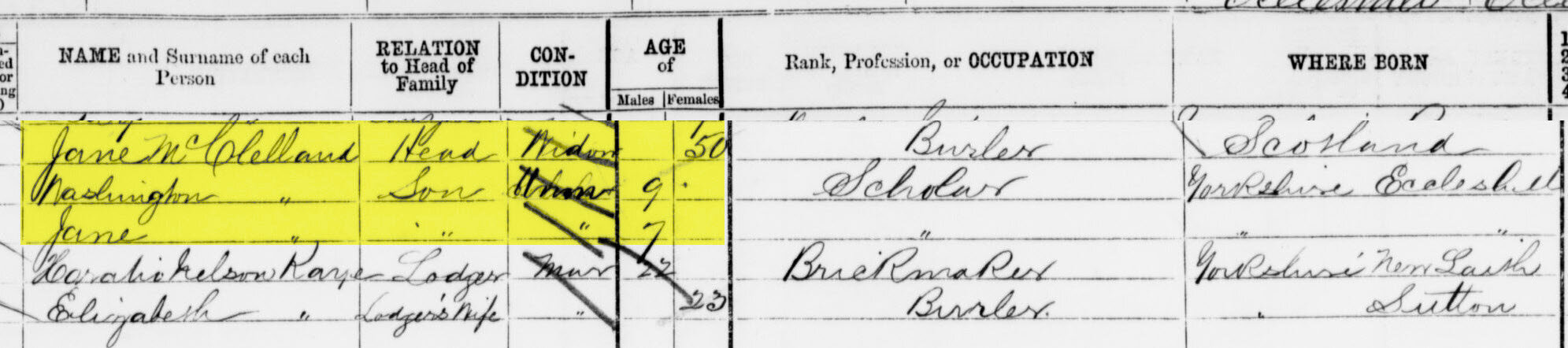

From this record alone, I can add John S., Thomas, William, Elizabeth and James to Washington’s family tree (see some caveats below on interpreting census records). But with Washington so young and his mother only 38 years old, I’m left to wonder whether the couple had more children. So I go to the 1871 census, below. One more child appears: a little sister, Jane. I also learn that Washington’s father has died (his mother appears as a widowed head of household):

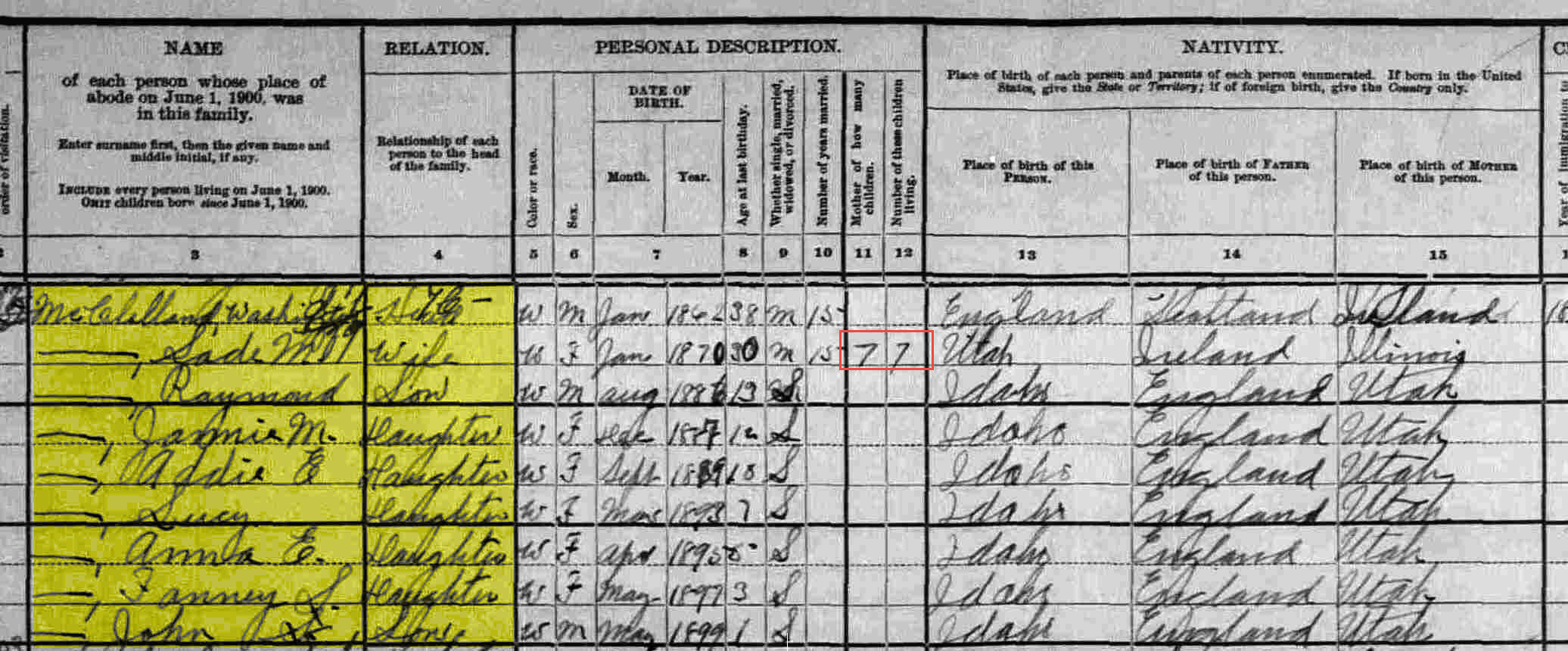

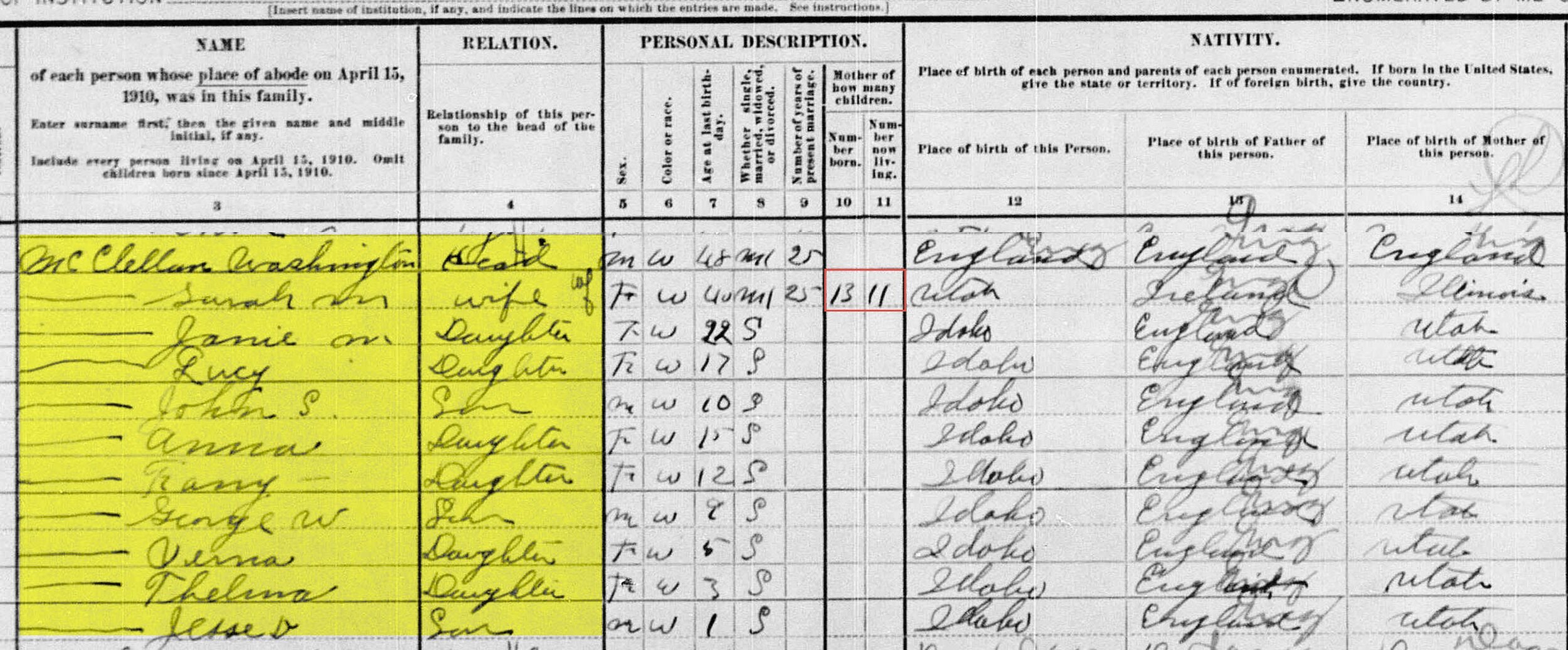

Not long after, Washington’s mother died, too, and he emigrated to the United States. The 1880 census shows him living as a single lodger in a distant relative’s home, and there’s no surviving entry for 1890. By the time we catch up with him in 1900, he’s the 38 year-old parent of many children with his wife Sarah:

Note: the 1900 and 1910 US censuses include how many children a woman had borne and how many were living at the time. I’ve boxed this in red. In 1900, Sarah reported having 7 children, and they all were alive.

Pushing ahead to the 1910 census, I can see that more children were born between 1900 and 1910. I also note that although the total number of Sarah’s children has risen to 13, only 11 are still living:

Washington died before the 1920 census, but Sarah appeared once more, in 1930. A quick check of that census shows no additional younger children living with her.

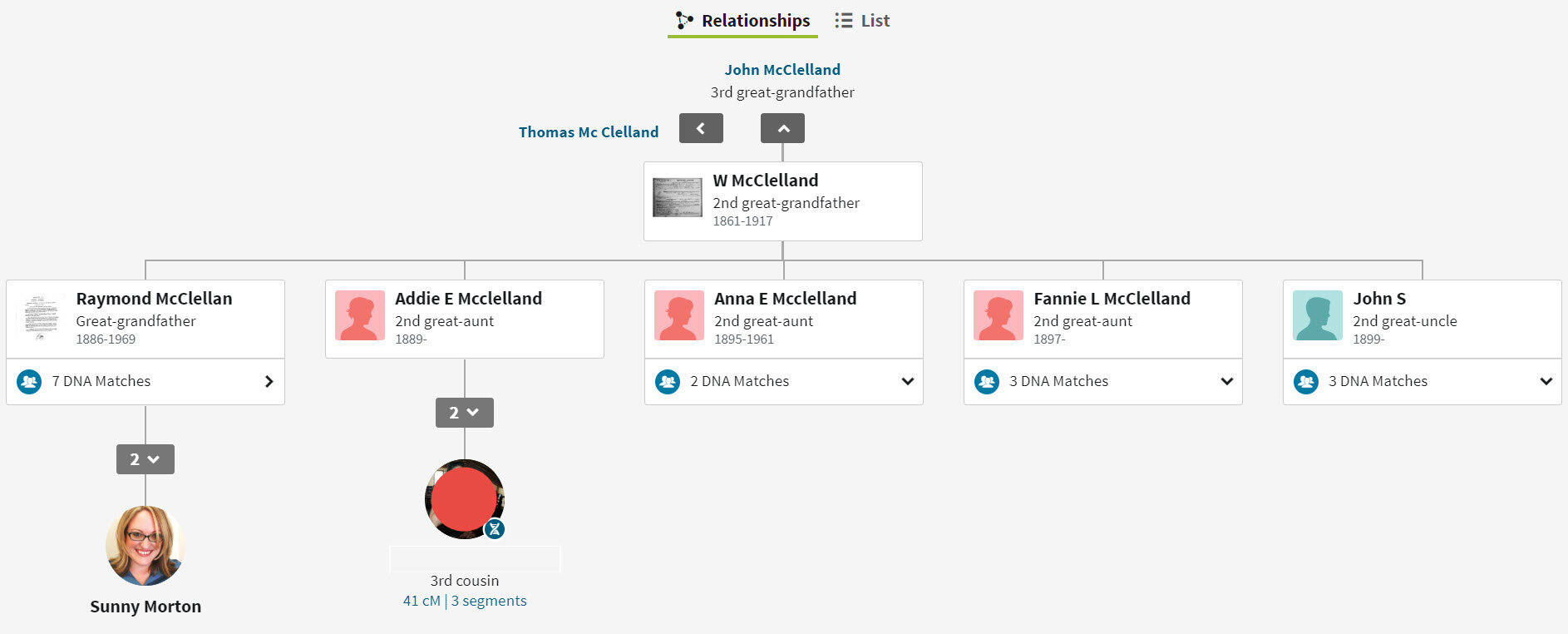

With all these new sibling names in mind now, it’s exciting to turn to my ThruLines tree reconstruction at AncestryDNA. It already suggests that I have several DNA matches who descend from Washington and a few of his siblings (hey, I’ve seen those names before!) as well as some who come through his father’s brother Thomas. As I build out all their family trees, I’ll become more confident in the accuracy of these suggested connections—and I’ll likely find additional matches who descend through this line.

Census records strengthen family trees for DNA matching

Follow these census research tips to build a family tree that will be stronger for your DNA matching experience:

- Look in every available census across a relative’s lifetime. Each may reveal something (or someone) new.

- Watch for evidence of blended families and half-sibling or step-sibling relationships. In the United States, you may see entries with how many years someone had been married and whether this was a first marriage (M1) or subsequent marriage (M2). The “relationship to head of household” column was specific to the person listed as head of household—usually the father, if he lived with the family. The relationship status applied to him: they could be his children from a current or previous marriage. A child who “belonged” to his wife only might be listed as a stepson or stepdaughter. Sometimes this distinction wasn’t made, however; it depends on how the family reported it and how the census-taker interpreted and recorded it.

- Follow each sibling across his or her lifespan in census records to:

- confirm half/step-sibling relationships,

- identify a sister’s married surname(s) (which may help you recognize matches),

- determine whether each had children (who would contribute to your DNA match pool),

- follow their trees forward in time as far as possible to make your tree even stronger for DNA matching purposes.

- Other clues in census records, such as birthplaces and names of grandparents or other relatives who may have been living with your ancestor’s family, can also help you reconstruct your tree. Note that I haven’t shown you the entire census entries, which often also reveal their locations, occupations, and other interesting details.

- Older census records tend to be less detailed. In the United States, for example, you won’t find relationship to head of household before 1880. However, census-takers in some earlier decades were instructed to list nuclear family members first, from the oldest to the youngest, followed by others living in the household. If directions were followed, you may be able to guess at sibling relationships and then confirm with additional research.

- I pulled the census records above from the free website FamilySearch (which hosts images of England’s 1861 and 1871 censuses courtesy of Findmypast). But census records are also available on other major genealogy websites, including Library Editions that may be available in a public or research library or Family History Center near you. You may also discover some state or local censuses, too.

- After finishing with census records, I would next look for vital records (birth, marriage and death) for each of these siblings in both generations. I’ll write another article with tips on researching vital records soon; for now, here’s a guide to U.S. vital records: for other countries and specific locales, search the FamilySearch wiki the name of the place and phrases such as “birth records” or “marriage records.”

- Watch for pictures that other descendants have shared in their family trees, like this one recently shared by David Higginson on FamilySearch, which shows several siblings whose names I can match up with that 1900 census:

Consider purchasing an Ancestry subscription to gain access to thousands of genealogy records that you can then easily link to ancestors in your family tree. Not sure an Ancestry subscription is right for you? Click here for a two-week free trial to Ancestry to see what you think.

Now add some DNA!

We’ve just covered some great tips on adding more paper records to your family tree. Now strengthen your family tree findings with DNA records. Don’t worry, with our help it’s easy. Get started with our free guide, 4 Next Steps for your DNA.